These Walls Do Talk – Civil War Graffiti and the Stories It Tells

Countless stories began and ended during the Civil War – stories told in letters home to mothers, sweethearts, brothers and sisters; experiences put to paper by lamp or firelight in diaries and journals; words shed like tears on the pages of survivors’ memoirs. But other stories were written in full view, archived on plaster walls of private homes and churches turned hospitals and headquarters. I visited two such places recently – Blenheim, in Fairfax, Virginia and Ben Lomond, in Manassas, Virginia, where soldiers left a bit of their stories.

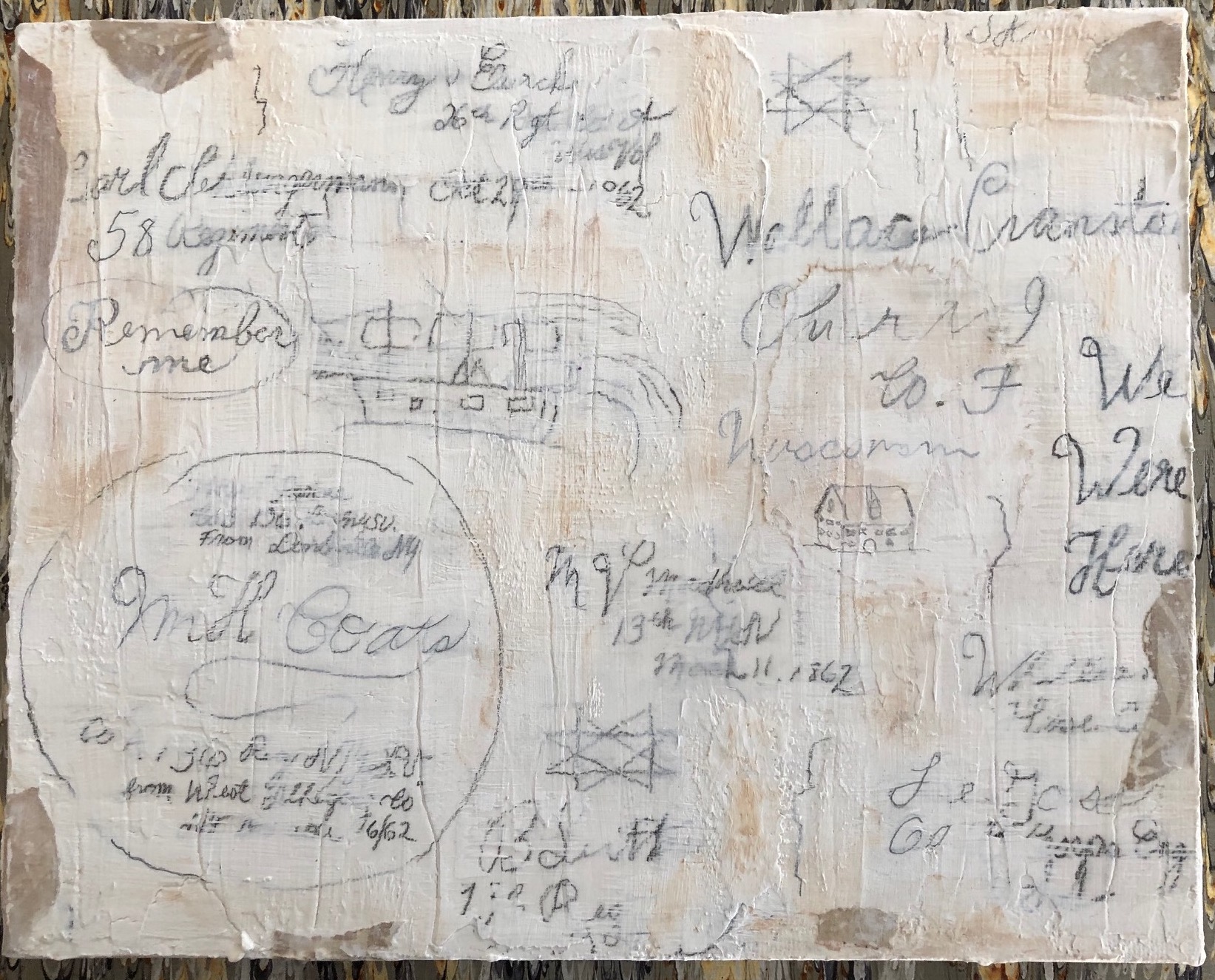

In March 1862, Union soldiers moved into Fairfax Court House, Virginia, very near Blenheim, and maintained control of the area for the duration of the war. Between September 1862 and January 1863, Blenheim served as part of the Reserve Hospital system for the 11th Army Corps. Many young men suffering from wounds and disease were treated here, including several from the 136th New York State Volunteers. Bruce Luther signed a wall in the Blenheim attic in December 1862, survived the war, returned to his hometown and married, but died in 1869 of tuberculosis. M. H. Coats, another New Yorker, gave clues to his time at Blenheim in his pension deposition. His signature, from December 1862, is easily recognizable on the attic walls.

Some wall signatures – when decipherable – give enough information to track a particular soldier through regimental histories, hospital records, and/or pension applications. (Their stories continue!) Pension files may also yield other treasures, such as Addison Muse’s small diary from 1863, detailing his story some months after signing the attic wall in March 1862.

Though through the years, the Willcoxon family painted and wallpapered over many of the signatures on the first and second levels of their home, the attic wall gallery remained pristine through four generations.

Benjamin Tasker Chinn built Ben Lomond and its outbuildings in 1832. The city of Manassas now surrounds the historic home, once part of the extensive Robert “King” Carter land grant.

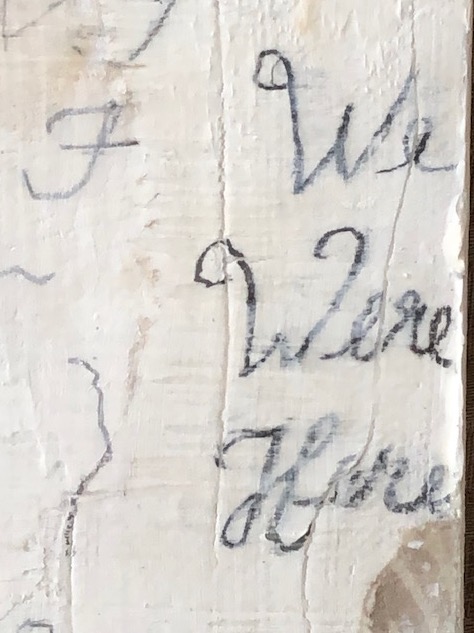

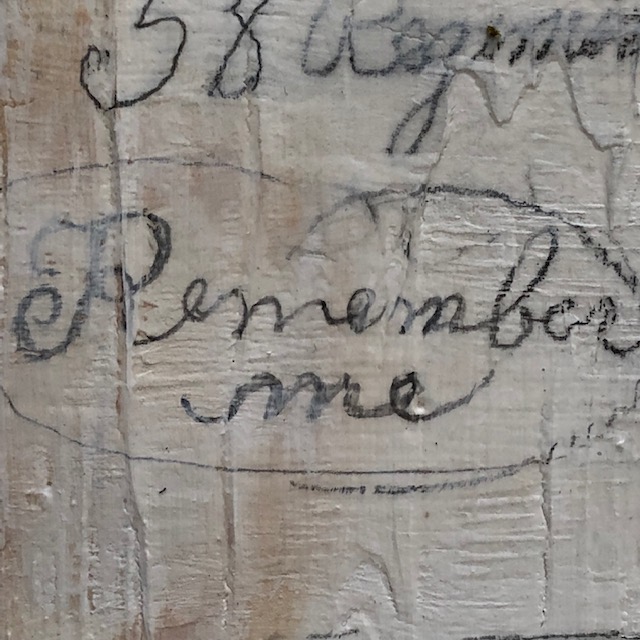

The home, constructed of local red sandstone, served as a field hospital during the Civil War. Visible on its walls – names, dates, and military units – graffiti tells a bit about the who of the story, though not the what or why. However, as with some of the names at Blenheim, research has allowed historians to “get to know” some of the signers.

William Wallace Cranston, an Ohio farmer before enlisting near the beginning of the war, autographed the upstairs wall in 1862. His unit, the 66th Ohio Infantry Regiment was in Northern Virginia from August 18 through September 2 as part of Pope’s campaign and also took part in guarding army trains during the second battle of Bull Run. Cranston reenlisted twice and served until the end of the war. He won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his courageous actions at the May 1863 Battle of Chancellorsville. Later Cranston moved to Parsons, Kansas, where he was elected to the Kansas House of Representatives.

As I continue my Civil War research and visit historic sites, I find the names I come across, such as Wallace Cranston, take on a certain energy, propelling me forward to learn and share their stories. Why did these soldiers write on walls? Perhaps for several reasons. But certainly for some, it was a way to express to those who would later read their words, “I was here. I had a name, a home, a family, and a story.”

For this week’s art, I wanted to represent some of the graffiti that I had seen at Blenheim and Ben Lomond. I recreated the plaster walls using modeling paste on canvas, then reproduced many of the signatures and some of the drawings that I found so captivating.