Maria and Metamorphosis: The Art of Maria Sibylla Merian

NOTE: This post is in honor of Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), whose work I discovered as I researched women pioneers in the field of nature art and writing. From the first paintings I saw of her flowers and butterflies, I knew my MSM odyssey had just begun.

Jacob Houbraken after Georg Gsell

In June 1699 Maria Sibylla Merian and her daughter, Dorothea Maria, embarked on an adventure that would take them from their home in Amsterdam to the Dutch colony of Suriname, to study and sketch dozens of insects and plants in their native habitat. Quite a remarkable voyage for two women at a time when sea travel involved incredible risks. Biology was forever changed as a result of Maria’s and Dorothea’s work and established Maria Sibylla Merian as a preeminent naturalist and painter. Many consider her the greatest botanic and insect painter ever. How I would have loved to meet her. Since that is not possible, you and I must learn of her fascinating story from her surviving art and writings. And what a beautiful story it is.

Maria was born in Frankfurt, Germany in 1647. Most likely she learned watercolor painting from her stepfather. Being very observant, she took notice of the caterpillars and butterflies she saw on the plants she painted. Maria began studying butterflies, letting the caterpillars pupate and emerge. In 1675, she published the first of three volumes of her well-studied watercolors of flowers, many of which included insects. In her 1679 collection, Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung (The Caterpillars Miraculous Transformation), she painted caterpillars and butterflies on their host plants, becoming the first artist to do so. Before 1668, when Italian Francesco Redi showed otherwise, it was thought that living things could arise from nonliving matter – i. e. butterflies from mud puddles. With her observation and study of caterpillars and butterflies, Maria was able to affirm Redi’s conclusions.

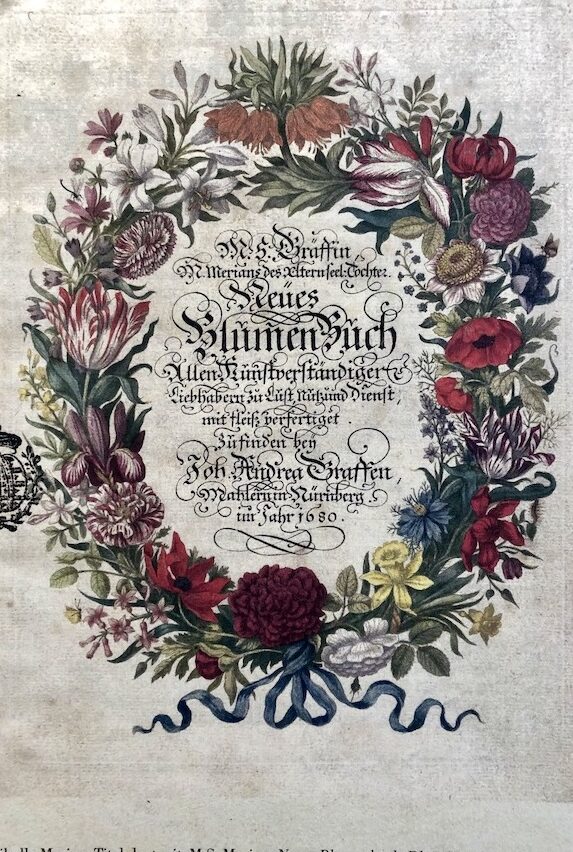

In 1680, Maria published the first of the three volume Neues Blumenbuch (New Flower Book) a collection of flower prints intended for her students and also for those who liked art.

After a stay in a religious community, where she first saw butterflies and animals brought from Suriname, and after a divorce, Maria and her daughters, Dorothea Maria and Johanna Helena, moved to Amsterdam where they were living by 1691. In Amsterdam, Maria began her atelier, or studio, where she and her daughters, who were also talented artists spent their days painting and breeding caterpillars. Maria gained much notoriety in Amsterdam for both her paintings and her research.

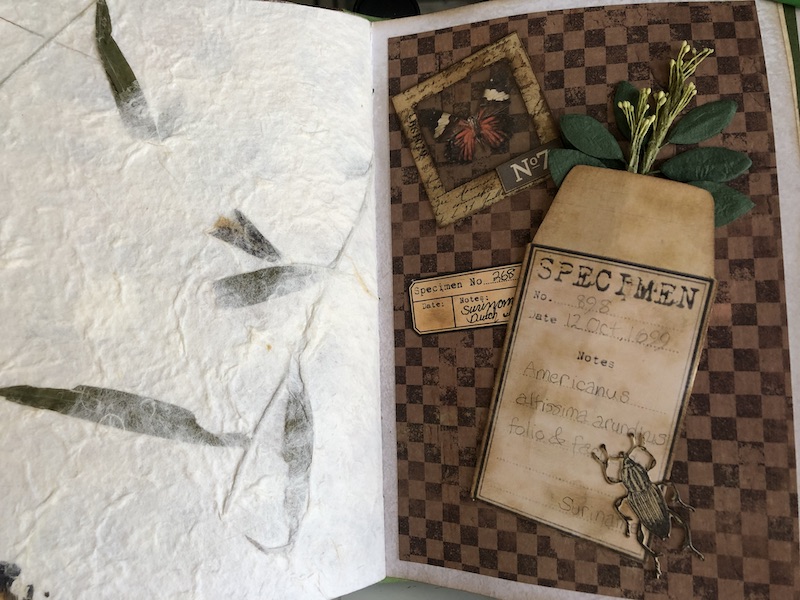

Amsterdam in the 17th century was a hub of trading activity, bringing goods from around the world, including the Dutch colony of Suriname. Maria, acquainted with some prominent citizens and collectors, spent time visiting their Cabinets of curiosities, some of which included insect and animal specimens from Suriname. Maria desperately wanted to see these creatures in their natural habitat, so she made arrangements for herself, then 51 years of age, and Dorothea, age 21, to travel to Suriname. Using Paramaribo as a base, the two intrepid naturalists studied in gardens as well as deep forests where trails had to be cut as they went. Maria writes to readers in the introduction to the Suriname book, “I there painted meticulously on vellum these 60 pieces from life with their observations. . .” Maria and Dorothea left Suriname on June 18, 1701, after Maria became ill because, as she wrote, “the climate in that country is very hot and the heat did not agree with me.” They returned to Amsterdam with a great deal of material for a book on insects of Suriname, as well as dried plants and insect specimens.

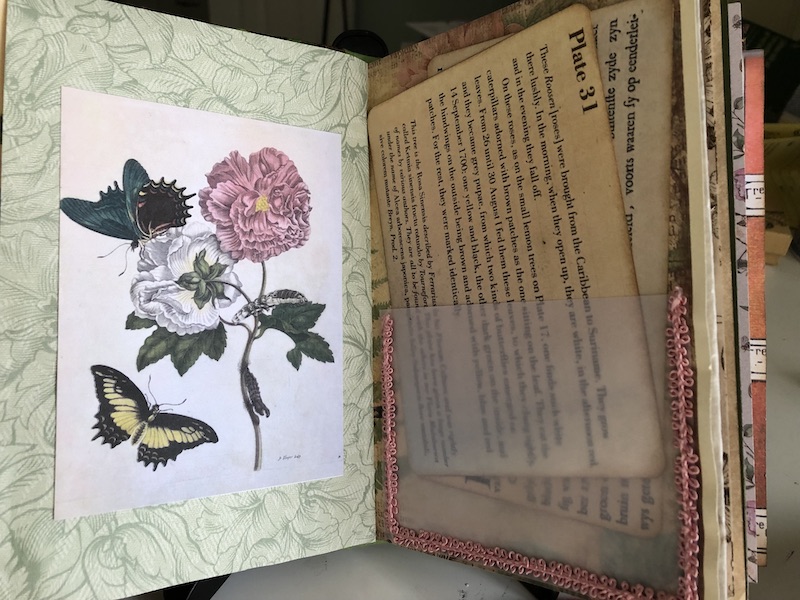

The process of getting the art and text ready for publication involved making copperplates for each piece. Plates were printed on rag paper (at the time made from old clothing). Each printed image was then hand colored – mostly by Maria, but some parts were finished by her daughters, using aquarelle, a thin watercolor.

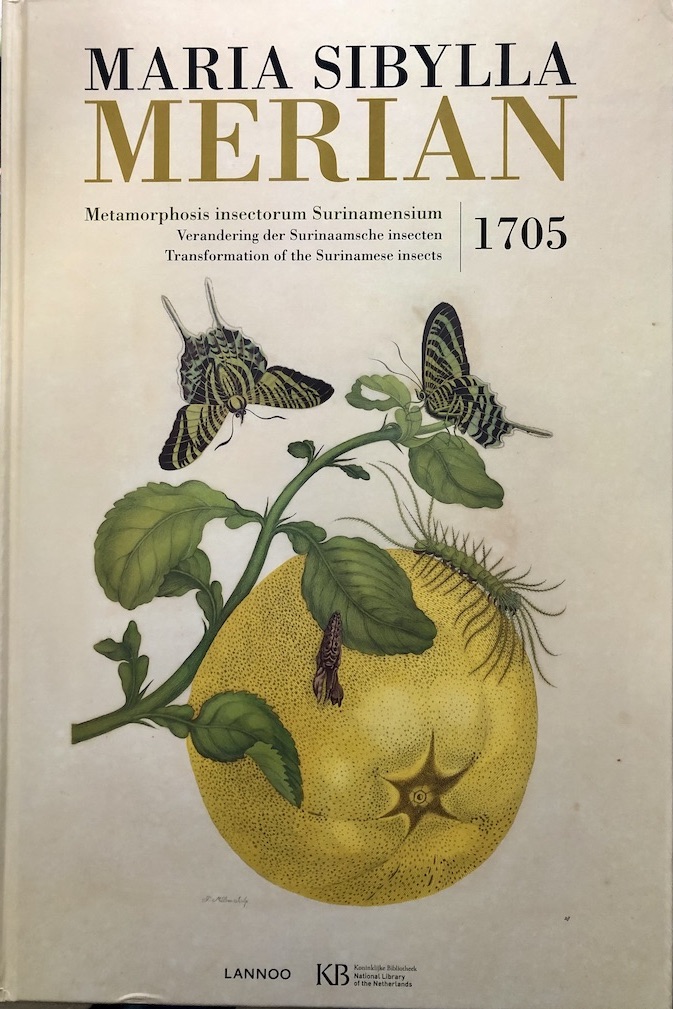

The culmination of their work in Suriname, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, was published in 1705 in both Dutch and Latin and contained 60 composed plates. The number of copies printed is not known, but 60 copies of the first edition of the book survive in public collections in libraries and universities around the world. It is thought that others may survive in private collections.

Maria’s popularity and the interest in Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium has only increased over time. In 2017, three hundred years after her death, a facsimile of the original volume was published through a collaborative effort between The National Library of the Netherlands and Amsterdam University. Size of the facsimile volume was kept the same as the original – 36cm x 54cm (14″ x 21-1/4″), and though large, it can barely contain the story of this incredible artist and naturalist who contributed so much to science.

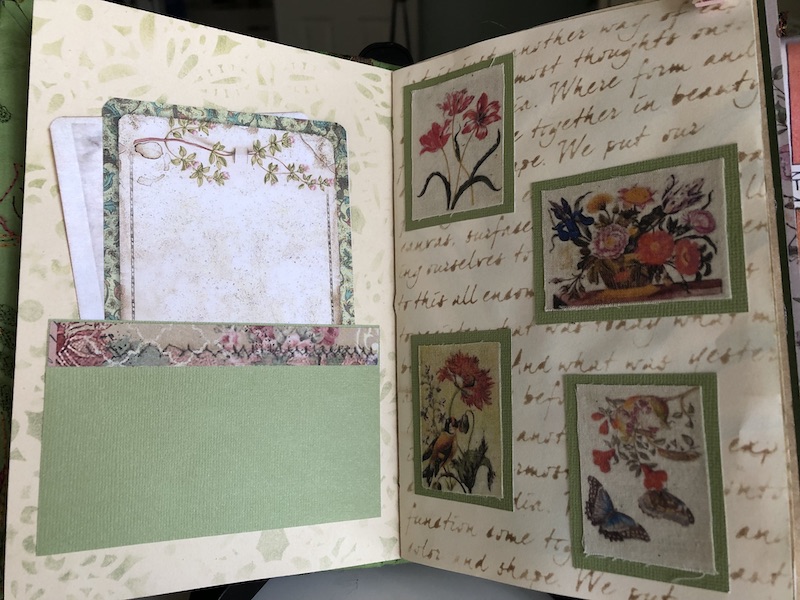

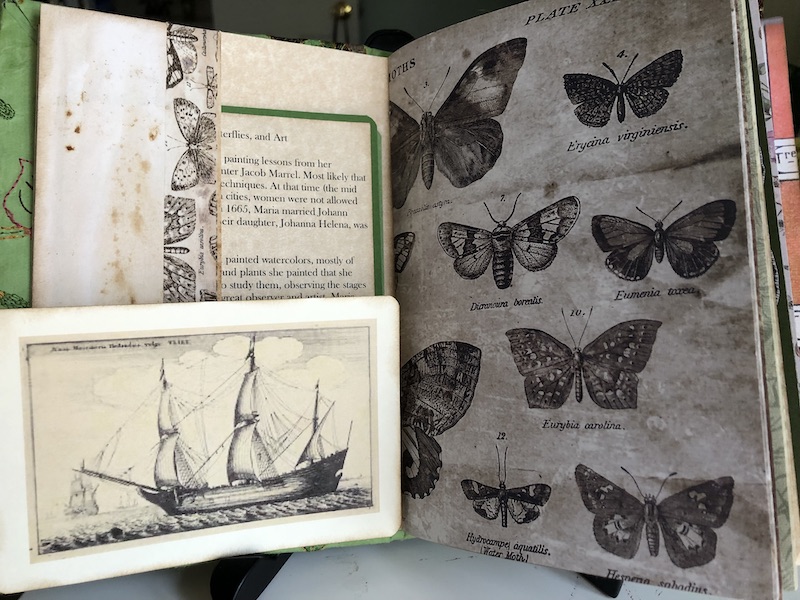

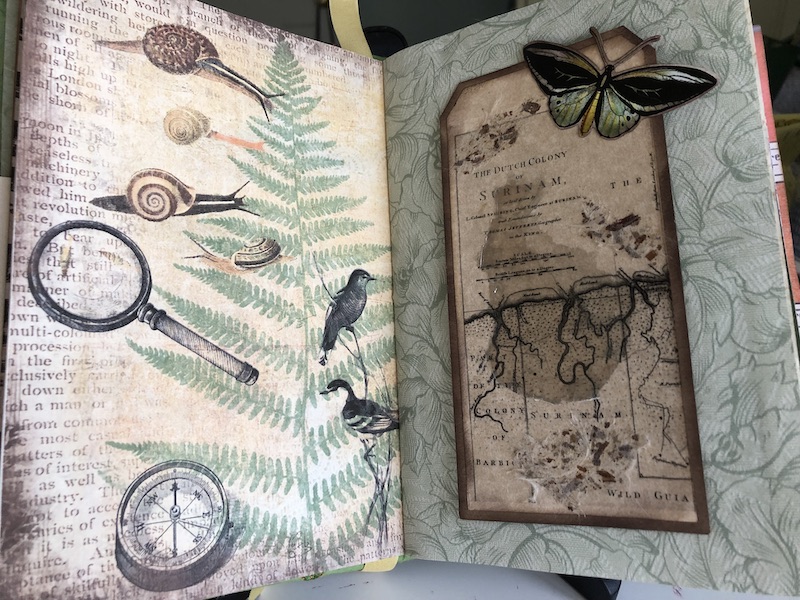

MY PROJECTS: I created two projects related to Maria’s love of butterflies and her trip to Suriname. The first project is a “spool book” using fabric, rubber stamps, and glass beads. For my second project I created an art journal (shown at the top of this post) featuring images and narrative on Maria’s Suriname adventure. I used several types of paper and images to create pockets, tags, and mixed media pages, a few of which are shown below.

Thank you so much for taking time to read my blogpost. Next time- another fascinating naturalist!