“Dear Arthur. . .Mother is Sending a Jar of Apple Butter” – Letters from the Civil War

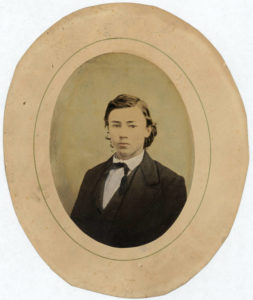

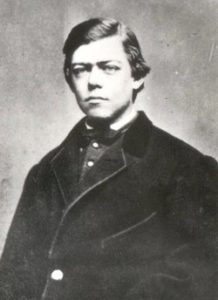

Lyman and Ruth Strong sent their thoughts and love (along with the apple butter) to their son, Arthur, on Christmas Day 1862, from Seville, Ohio. Arthur had enlisted in November, 1861, at age 16, one of thousands of young men who would receive letters from home and reply with their own.

In researching my latest book on the Civil War in Northern Virginia, I have been fortunate to read many wartime letters and diaries – words of ordinary people caught up in extraordinary circumstances. Hundreds of volumes have been written about the war, but perhaps the most poignant record lies in the correspondence between home and battlefield.

Sometimes I feel like an intruder as I read these personal documents. Words come to mind to describe these precious messages: sweet, tender, and caring. Other times they were informative, instructional (see below), and sad.

Ruth Maria Strong, in a letter to Arthur, dated February 17, 1862 wrote:

“I sent you one pair of socks, which Mother knit for her soldier boy, may he live to need more. . .”

Later in the same letter, Ruth gives Arthur advice on how to stay healthy, as she has heard about typhoid outbreaks. Then, with a mother’s concern, she warns Arthur about forming bad habits while he is gone, praying that he returns to them as he left, “free from the vices that surround him.” His father gave advice on keeping dry. “Purchase a rubber blanket lined with flannel.” Clean clothes were on their way so that Arthur could have his photo taken in “civilian dress”.

Arthur did not return to his parents. He died of dysentery later in February, in a Union hospital in Ashland, Kentucky.

Capt. James Sayles wrote many letters to his sweetheart, Florence Lee. In a letter from June 11, 1864, he wrote

“I wonder how you are passing away the long pleasant summer days! I hope you are enjoying yourself.”

And, in closing of the same letter,

“I am getting tired and sleepy after my ride of about 35 miles today. . . wishing you pleasant dreams, I will retire to dream of my darling Florence.”

Capt. Sayles of the 8th New York cavalry, died in battle on June 23, 1864.

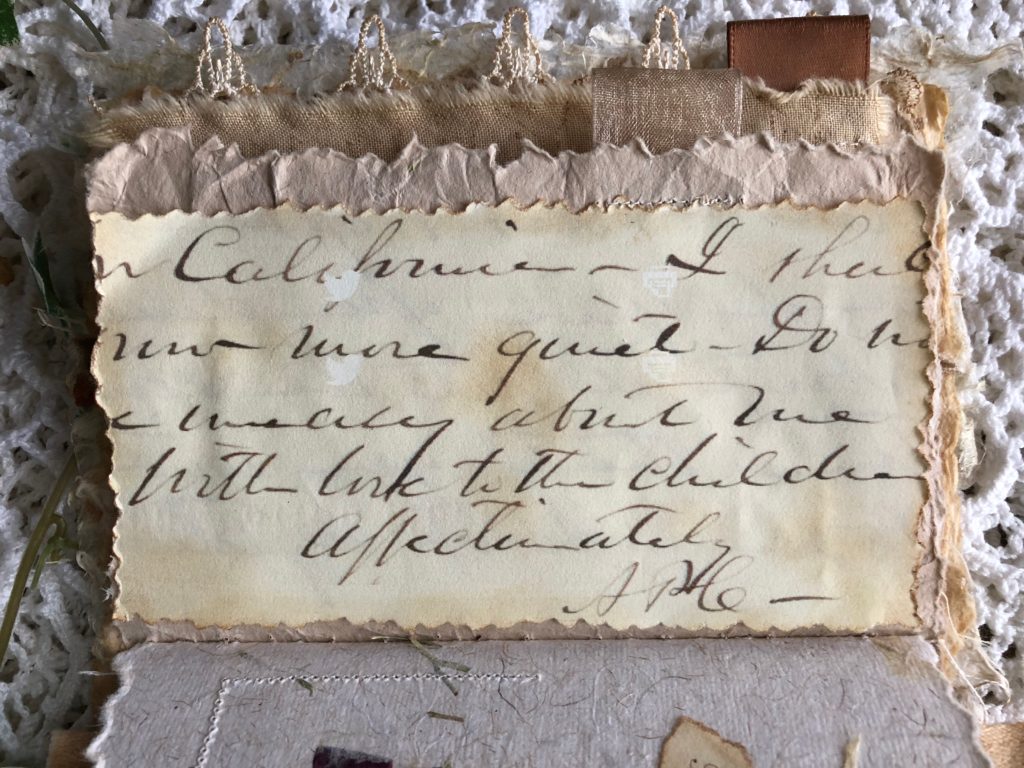

Other soldiers did return home and went on to live long, productive lives. Hazard Stevens, of the 79th New York Infantry Volunteers, went on to win the Medal of Honor for his actions in the war. And, in 1870, was part of the first documented ascent of Mt. Rainier. He wrote to his mother, Margaret, in September, 1864, from Clifton, Virginia, describing the camp location

“We have a most beautiful little camp for Headquarters, and are quite comfortable. . . We have plenty of grapes, peaches and apples and I found some sweet cider a few days ago. So you see we are very well off as far as physical comfort goes.”

This must have brought relief to Margaret. Many other soldiers, including Samuel D. Lougheed, wrote instead of the horrors of war and the dead and dying without anyone near “to speak a word of comfort.” Lougheed, a Union Army chaplain lived until 1893.

Wartime correspondence took on a more intense and expressive tone, as dictated by the circumstances the writers found themselves in. A letter might be the final words received or written. Words had immediacy. Writers and recipients shard the same incentives for writing – loneliness, worry, fear, love, and the need to share the story of the moment – from their minds and hearts.

Letters also provided news of the war. But wartime presented delivery problems and correspondents wrote not knowing if letters would get through. To sustain hope, the writer needed to believe their words were not in vain, and would bring comfort across the miles.

Time spent with these letters brought sadness, but also gave me a greater understanding of individual stories. That, to me, is where history resides.

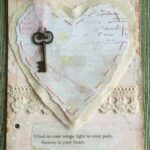

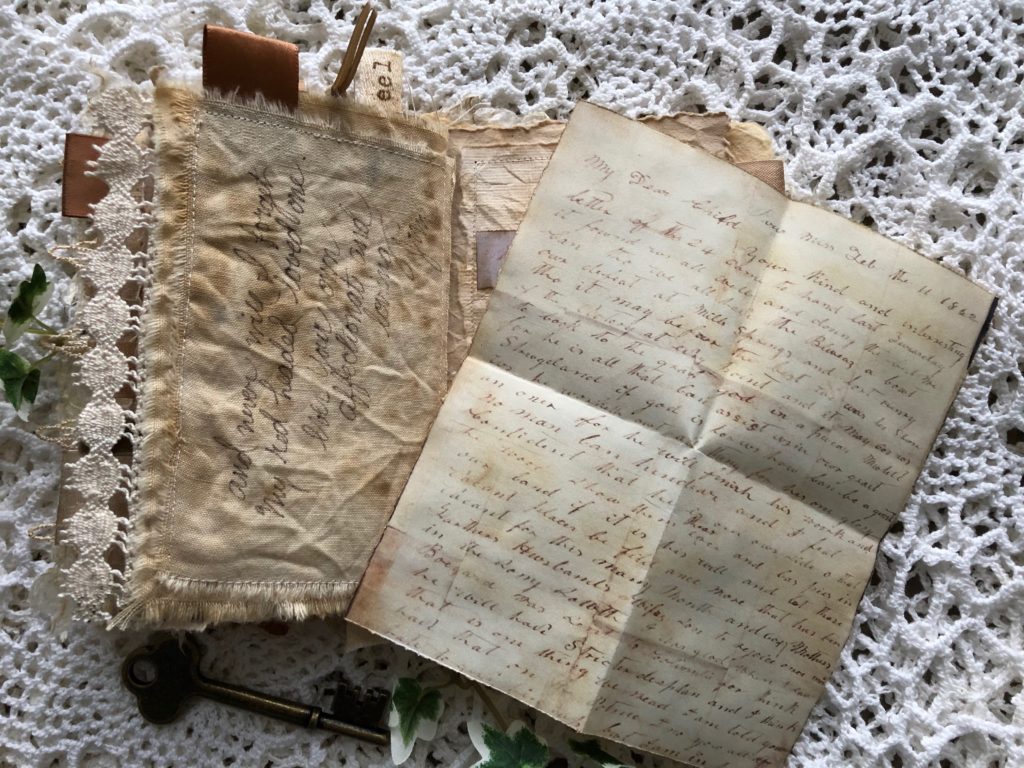

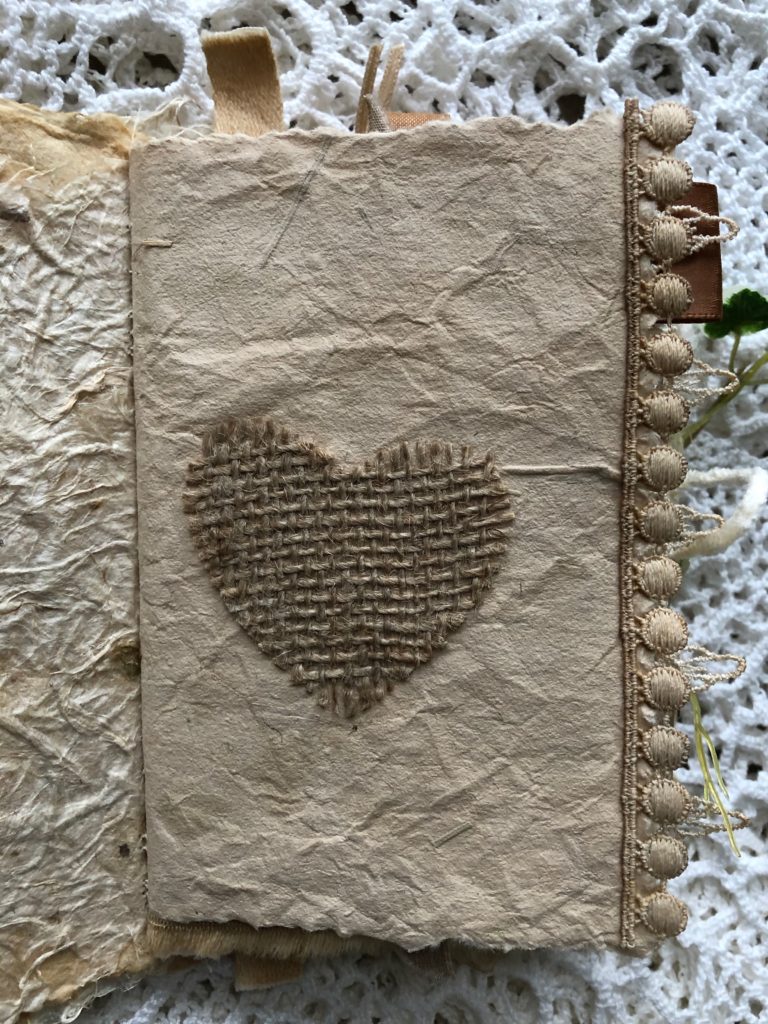

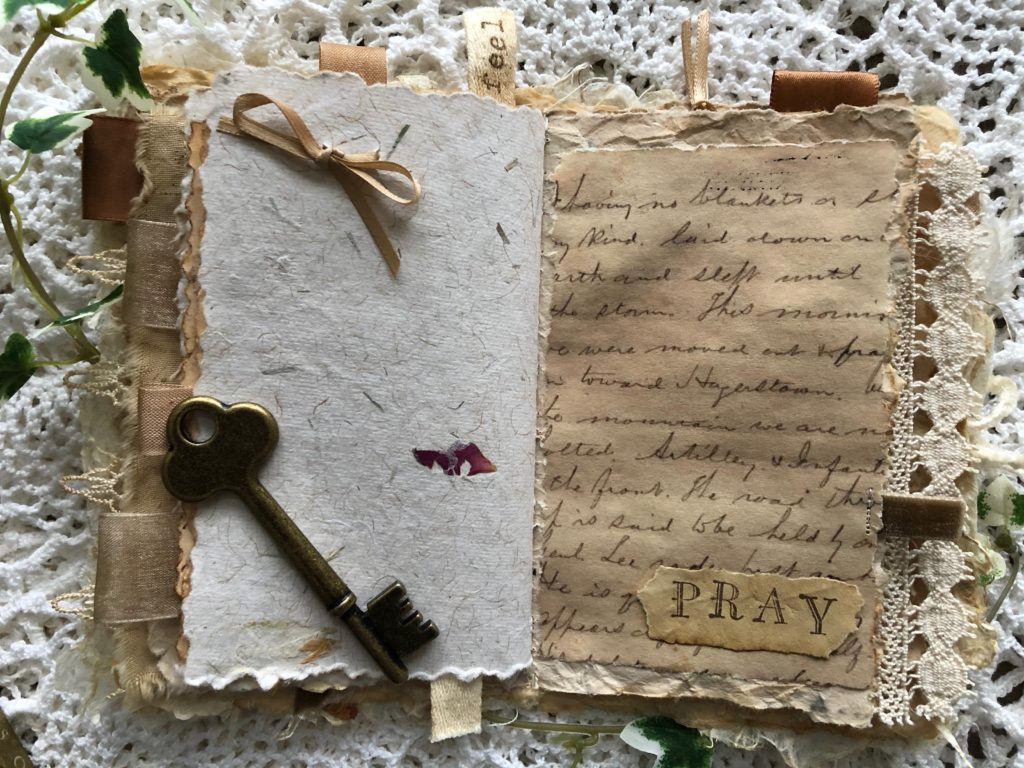

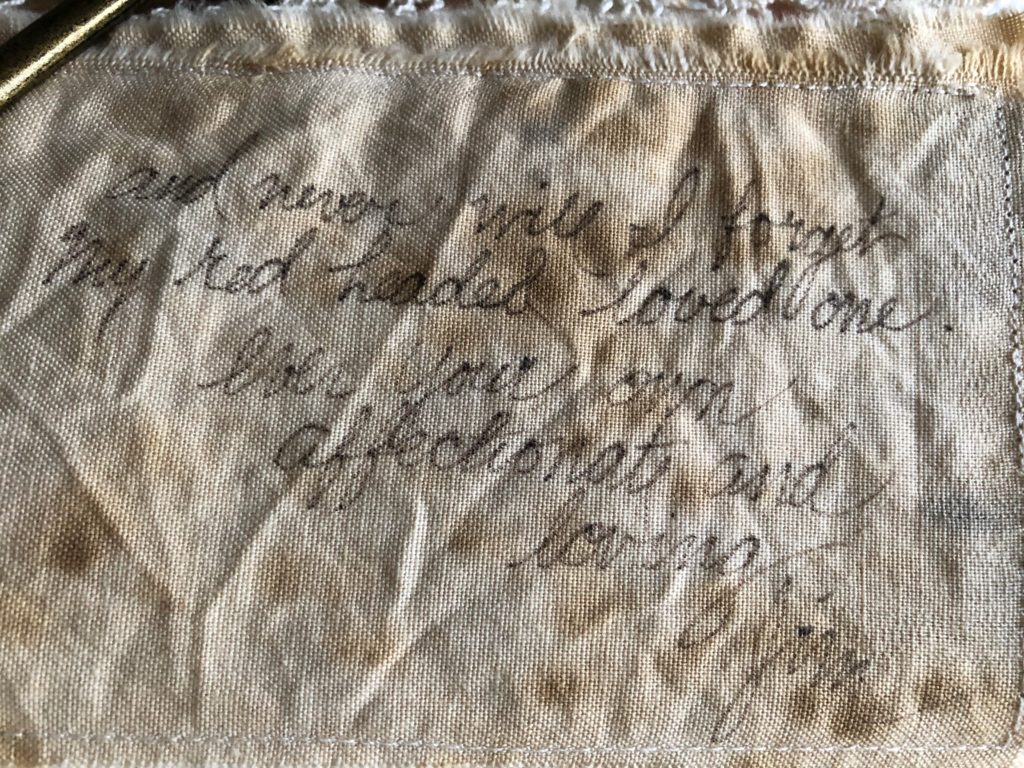

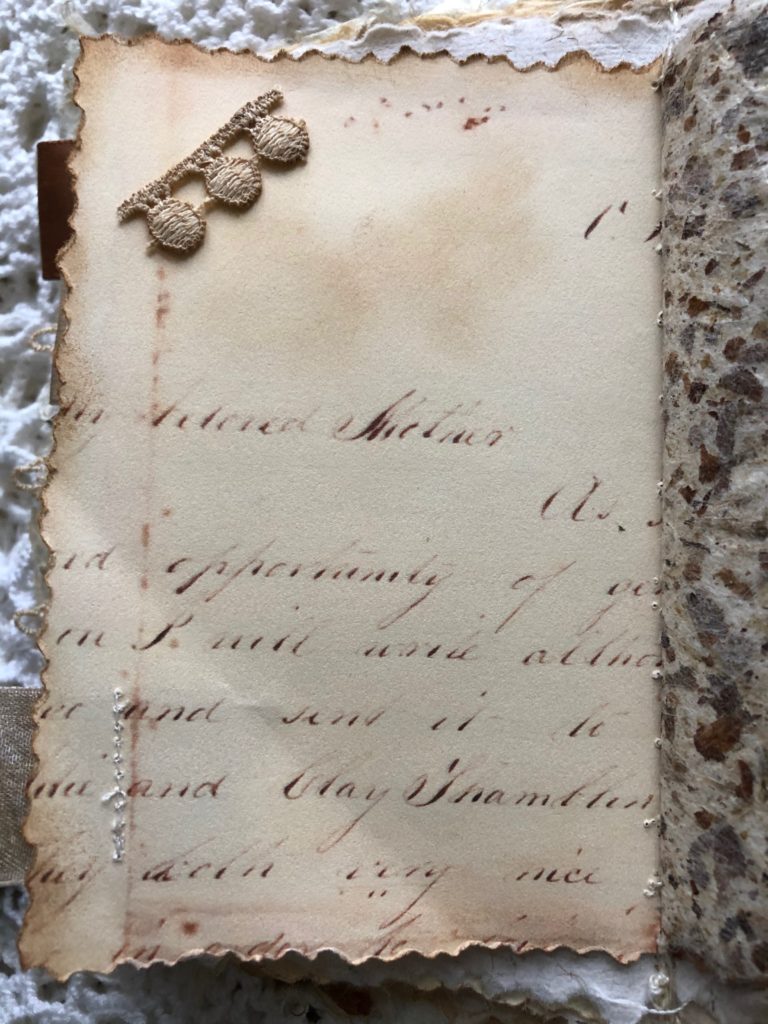

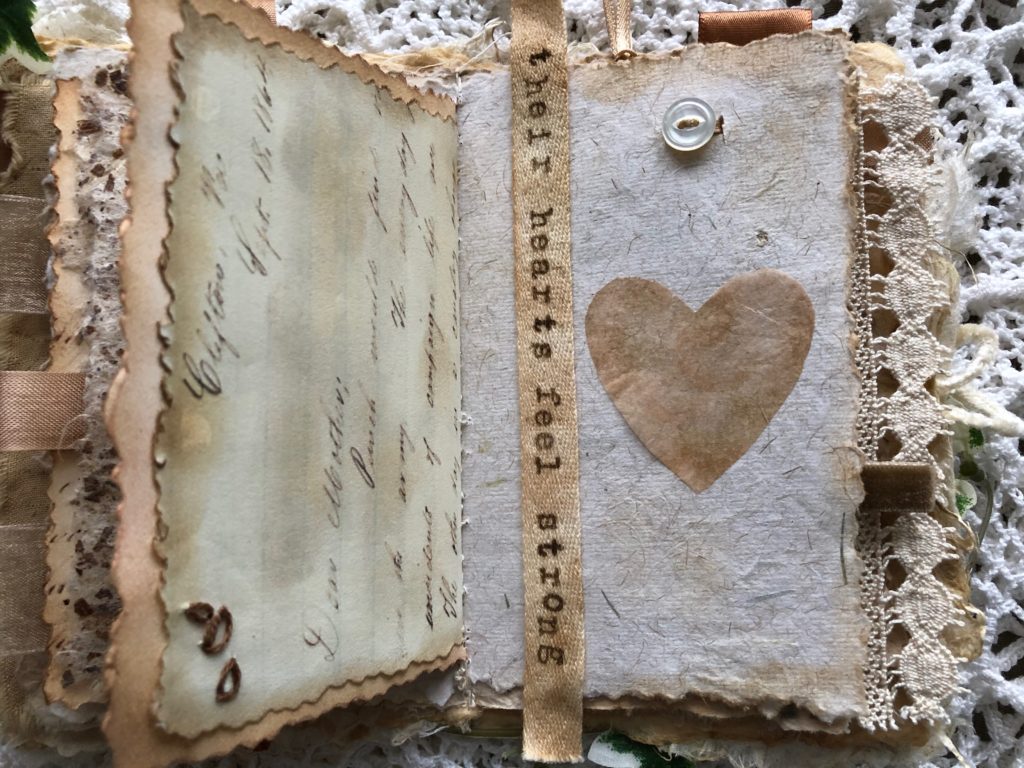

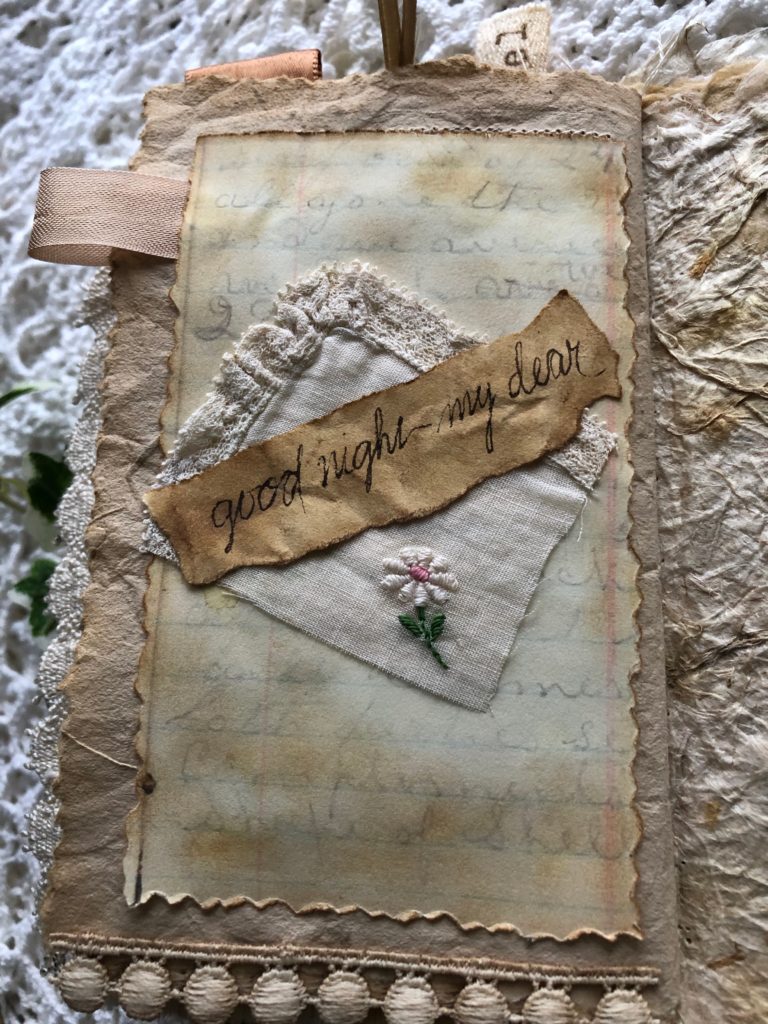

This week’s art brings words from Civil War letters together in a little handmade book. I wanted to evoke the feeling of letters, brown-edged and delicate with age, like a sweet treasure discovered in an old trunk.

To give papers, fabric, and trims an aged look, I stained them with tea and coffee. I used various papers, varying the sizes to add more texture and interest. I stamped the dyed muslin and paper pages using distress ink and a text rubber stamp. Individual words were selected from letter text and stamped or written with sepia ink. I sewed dried rose petals inside tulle pockets and added buttons on other pages. On the last page, “Good night, my dear”, I added a bit of an aged handkerchief to make the words even more personal.

Finally, I wanted to protect the delicate pages, so I sewed in ribbon tabs. To bind the pages together, I hand-stitched down the center,using embroidery floss. This wee little book took time, but it was a labor of love. Please send me a comment if you have questions. I would love to hear from you.