A Natural Influence: Nature and the Brontë Sisters, Part Two

Part Two: Charlotte and Anne

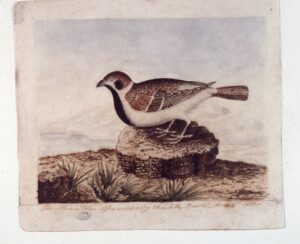

Above print from the original image “Country Scene with Cattle” by Anne Brontë, 1836. Pencil. Original art courtesy of the Brontë Parsonage and Museum.

Note: This is part two of a three part series on the Brontë sisters. Part one found my husband and I in West Yorkshire, England, following in the footsteps of the Brontës on the moors near Haworth.

“My sister had a particular love for them, and there is not a knoll of heather, not a branch of fern, not a young bilberry leaf, not a fluttering lark or linnet, but reminds me of her.”

Gaskell, Elizabeth, The Life of Charlotte Brontë. New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

After my walk out over the moors last year, I felt the power that the wild landscape can have on one’s soul, and that was after just one day. The Brontës experienced the moors – the weather, flora and faun, – for decades, beginning in 1820. The scenery played a significant part in the creative endeavors of the talented sisters – Charlotte, Emily, and Anne – and their brother, Branwell.

Patrick Brontë, curate for Haworth and vicinity, took a keen interest in his children’s education and development, encouraging reading, discussion, and imagination. The family owned many books, including Thomas Bewick’s The History of British Birds and The Gardens and Menagerie of the Zoological Society Delineated, embellished by young Anne’s margin sketches. The children also had access to books from the lending library in Keighley, and the Keighley Mechanics’ Institute Library, where their father was a member. Both would have had popular books on natural history and birds, subjects their father loved and shared with them.

Courtesy of the Brontë Parsonage and Museum.

The Brontë siblings received some instruction from art tutors, but the young artists also studied and copied from drawing manuals and botanical illustrations. These drawings appeared in the first plays and writings, tales of Glass Town and Angria, begun in 1829, and was just the beginning of nature’s influence in each of the Brontë sisters’ body of work.

Charlotte

In Jane Eyre, published in 1847, Charlotte uses over 100 bird references, including the metaphore of Jane as a dove, linnet, and skylark, and Rochester as a royal eagle. In chapter one, a young Jane expresses how Charlotte may have felt about one of her own favorite books, The History of British Birds: “With Bewick upon my knee, I was then happy. . .” Jane refers often to passages and engravings in the book that provided a means of mental escape from her mean cousins and aunt. Later, while living at Lowood School, she again uses nature as a distraction for her difficult life there:

“. . . that bright May shone unclouded over the bold hills and beautiful woodland ou-of-doors. It’s garden, too, glowed with flowers; hollyhocks had sprung up tall as trees; lilies had opened; dahlias and roses were in bloom; the borders of the little beds were gay with pink thrift and crimson double-daisies; the sweet-briers gave out, morning and evening, their scent of spice and apples. . .”

Bronte, Charlotte, Jane Eyre. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2005. First published 1847.

Charlotte enjoyed drawing and painting, often from nature – sometimes sketching out on the moors or at the waterfall nearby. As mentioned earlier, she also drew from books, like her favorite Bewick’s. Here is one such sketch, that I have printed onto a hosta leaf.

Original image courtesy Brontë Parsonage Museum

Image printed onto hosta leaf.

Copyright 2020 L. Johnston

Anne

Anne Bronte saw the beauty in the details of nature. Her poem, “The Bluebell”, describes the Harebell, or Scottish bluebell, found in northern England and Scotland. Here is the first verse:

A fine and subtle spirit dwells In every little flower, Each one its own sweet feeling breathes With more or less of power. There is a silent eloquence In every wild bluebell That fills my softened heart with bliss That words could never tell.

“The Bluebell” by Anne Brontë. Stanza 1

Anne’s love of trees and the sea, often subjects of her drawing and painting, are also favorites of Helen Huntingdon, heroine of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Anne’s second novel. Helen’s art gives insight into her character. A passage in chapter 6 describes Helen as she sketches trees and in chapter 8, she speaks about capturing the light and colors of the trees on canvas.

One of Anne’s own drawings, “Country Scene with Cattle” is the image in our featured art this week. Original image courtesy of the Brontë Parsonage Museum.

Coming next: Part Three – Nature in Emily Brontë’s work AND a bit about the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth.

My thanks to the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, England, for their assistance with images.

*****

This week’s art: One of my favorite art techniques ever – Chlorophyll Printing! I learned this process last summer in a class taught by Robert Schultz, at the Center for the Book in Charlottesville, Virginia. I feel the Brontë drawings really lend themselves to this technique. See the two leaf images above. The hot summer sun does most of the work, transferring the image directly onto the surface of the leaf. The challenges are preparing the image properly and getting the “sun exposure” time right. More leaf images under Art and Journals drop down box.